Leia a seguir reportagem de Shannon Sims para a National Geographic, publicada em 19 de abril:

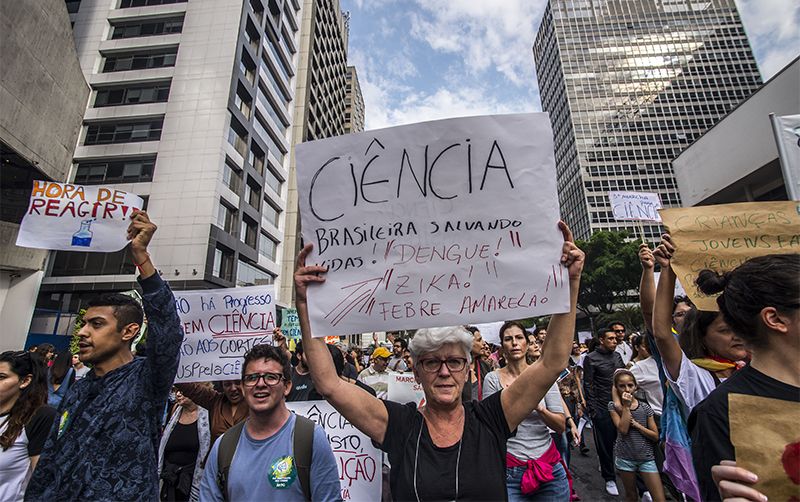

Scientists in São Paulo, Brazil, protest deep cuts in their funding. Photograph by Cris Faga, NurPhoto via Getty Images

When Jair Bolsonaro began his presidency of Brazil in January he quickly began making good on his campaign promises to rollback protections of the Amazon rainforest and indigenous rights and prioritize expansion of agriculture and business interests, setting off alarm bells among conservationists. And more recently he has been pushing deep cuts in scientific research programs.

Still, no one expected he would have such a dramatic impact on the career of 25-year-old scientist Alessandra Camelo.

“All I have ever wanted to be is a scientist,” says Camelo.

After earning her undergraduate degree in agricultural and environmental engineering, she placed into the master’s program for energy at one of Brazil’s top research universities, the University of São Paulo. Since then, she has spent a year studying environmental engineering at the University of Chicago and worked as a visiting scholar at Texas A&M’s bio energy testing program.

Her focus has been on finding a way to make ethanol production more efficient. Her career goal? “I want to use science to bring large-scale sustainability and strategic value to Brazil.”

The only thing standing in her way is Brazil itself.

Earlier this month, Bolsonaro announced that the budget of the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communication would be cut in half and that scholarship programs for the National Council on Scientific and Technological Development, called CNPq, the primary scientific research agency in Brazil, would be cut as well.

The budget for CNPq, which supports the scholarships of 80,000 Brazilians, had already been drastically cut earlier this year shortly after Bolsonaro’s inauguration. Now, the situation for these students is dramatic: the expectation is that all funding will run out by July of this year, with no plan for new funding in the future. (Read about Bolsonaro’s emerging Amazon policies.)

Brazilians anticipated that Bolsonaro would clamp down on the cultural and academic funding supported by his leftist predecessors, but even the president of the Brazilian Academy of Science, Luiz Davidovich, says he was surprised by the new reductions. He says that Bolsonaro promised in a letter to the academy prior to his election to nearly triple the government’s investment in research and development. “This cut goes against his promise,” Davidovich says.

“I am personally very worried with the situation we have in science and innovation in Brazil right now,” says Davidovich. “Students will lose their scholarships to study, and those who can still study will be forced to use obsolete equipment or to stop the research they have been conducting.”

Mercedes Bustamante, a professor at the esteemed University of Brasîlia who specializes in ecosystem studies, notes that researchers in Brazil are already under pressure to help the world understand the impacts of climate change and global warming. She says that even though the environmental research community in Brazil has strengthened in the past two decades, “now they face great challenges in continuing their research, especially those involving field research in remote locations, maintenance of field research equipment, and more sophisticated laboratory analyses.” “Twenty percent of the biodiversity of the world is here in Brazil,” points out Davidovich. “Our research is what protects that biodiversity; it’s how we find cheaper medicines, and technology to reduce deforestation. This cut doesn’t just harm Brazil, it harms the world.”

Hard-working students

Via CNPq’s scholarship program, masters students across the country receive 1500 reais ($382 USD) a month to attend public universities; doctoral students receive slightly more, 2200 reais ($560) a month.

Many students, like 23-year-old Mariana Ciotta, anticipate falling back on family support to continue their studies. Ciotta studies at the University of São Paulo, where she focuses on identifying rocks that could assist in carbon capture. She says that it is not just the individual financing that is at risk with the cuts, but also Brazil’s body of scientific research as a whole.

“I think a big issue is the uncertainty of the continuity of our research. If you believe in climate change, you should ideologically want this work to continue with the researchers who come after me and, in the long term, with projects that complement and contribute to my research. Instead, it will end.”

Thiago Gonçalves, a professor of astronomy at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, shares his perspective. “In science, you don’t finish projects in a couple of months. Science takes years of work and long-term planning. For me, the worst part is how science in Brazil is subject to the whims of the government at any moment in time. One day we have funding, and the next day, we don’t.”

Gonçalves explains that while in Europe and the U.S. researchers may draw on funding from nongovernmental entities, “in Brazil the access to private sources of funding for science is practically zero, so we really depend on the government here.”

“If we lose the scholarship students, we lose the labor force we need to do our research.”

Camelo, the bio energy student, is an example of someone who will be acutely impacted by the cuts. Unlike Ciotta, Camelo’s family cannot support her work. Camelo is from a small town in the interior of Brazil’s southernmost state, Rio Grande de Sul, where, she says, her family barely has enough money to keep the lights on, much less bankroll her university bills. So she waitressed and hustled her way through high school, and today she is proud that she is the first member of her family to attend public university (in fact, she’s the first member of her family to live outside of the state). The $382 she receives every month is intended to cover all academic and living costs in São Paulo, one of Brazil’s most expensive cities.

Now, with the proposed cuts, she expects all of her university funding to dry up by July, leaving her without a path forward, despite her sterling resume. “There is the perception that we [scholarship students] are somehow flying high with this funding, living the life,” she says. “In reality we are working hard and can barely afford our food.”

Difficult choices

For people in Camelo’s position, everything they have worked toward will suddenly disappear without funding, effectively ending otherwise promising careers. The economic recession that Brazil has been lumbering through for the past couple of years won’t help; those students will be tossed back into a depressed job market, with resumes that impress in the labs, but are ill-suited to most jobs. As a result, the cuts could create a ripple effect across the Brazilian economy.

But some students have one other option: to leave Brazil. Students like Camelo whose academic capacity outstrips their financial support, are now looking abroad—to Europe, to the U.S.—for ways to continue their masters and doctoral research. Bustamante adds that this migration of Brazilian researchers abroad “compromises renewal within the ranks of environmental scientists in Brazil.”

Camelo is one of the lucky ones. Her stellar resume has secured her a spot at a research institute in Germany for 3 months this year, long enough, she hopes, to tide her over until Christmas. She is hoping to thread the needle: to shine brighter than all of the other domestic and global candidates in Germany – many who, unlike her, speak fluent German – and somehow win a spot in a German doctoral program. She readily admits she is reluctantly being forced to become a part of a scientific Brazilian brain drain.

“I feel so bad right now, I feel like trash as I look into my future,” Camelo says. “It’s like everything that I have been working toward doesn’t matter anymore.”

“But I know who I am, and I know that I work hard. I will continue toward my dream to become a scientist. I’ve had that dream since long before this administration.”